Envelopes and Envelope Generators

Consider what happens when you play a note. The

volume goes up to some value, then eventually falls to

nothing, with some sort of reasonably well defined pat-

tern that is characteristic of the particular instrument.

For example, a low note on a pipe organ starts slowly

when you press a key due to the time the column of air

takes to build up in the long pipe, and the note takes a

while to die away as the column of air collapses in the

pipe. In contrast, a note played on a wood block starts

quickly as the mallet strikes the block, and dies quickly

as the block stops resonating. The overall pattern of the

volume when you play a note — how loud the note

becomes at any instant, and how long it takes to change

in level — is known as the "volume envelope." Organs

and wood blocks have very different envelopes. With

some unusual "synthesizer" voices, a note may not end

at zero volume, so the next note won't start at zero

volume. In some cases, notes can start at maximum,

then go to zero when you press a key then come back

to maximum level when you release the key; These are

exceptions to the rule, and such notes still have enve-

lopes, even if they are inverted.

Similarly, changes in timbre occur from the onset of a

note to the time it dies away; these changes can also be

defined by an envelope.

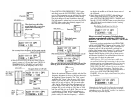

In the DX7, each of the 6 operators can be pro-

grammed with its own envelope. Generally speaking, if

an operator acts as a carrier in a given algorithm, its

envelope controls the volume of the note. If an algo-

rithm acts as a modulator, its envelope controls the

timbre. (This is a useful conceptual model, although

somewhat of an over simplification.)

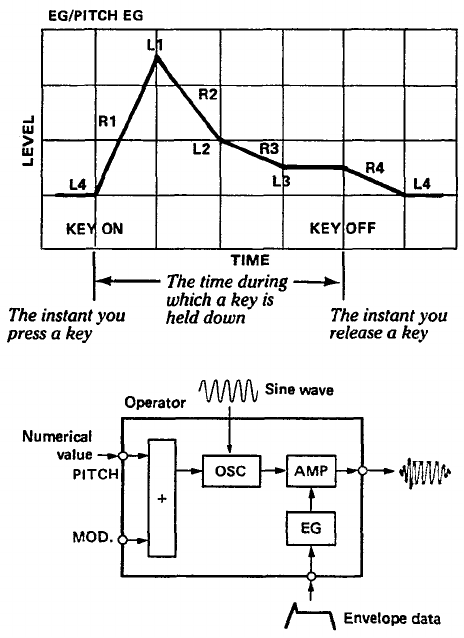

Illustrated here is a copy of the envelope diagram near

the upper right corner of the synthesizer front panel. We

have a few additional notes of explanation. The illustra-

tion is an aid to visualizing the DX7 envelope settings as

you program or edit a voice. There are actually trillions

of possible envelopes you can define with these EGs.

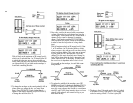

Each envelope generator in the DX7 permits you to

set 4 different LEVELs and to set 4 specific RATEs at

which the envelope moves from each level to the next.

We use the term "level" rather than "volume" or "tonal

value" because the envelope of the operator you're

adjusting could affect the volume or timbre depending

on the operator's location within the algorithm.

LEVEL 1 (L1) is the level to which the operator begins

moving as soon as you press down the key The opera-

tor may reach L1 almost instantaneously, or it may take

over a half a minute to reach LEVEL 1, depending on

the setting of RATE 1 (R1).

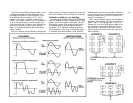

NOTE If you are familiar with analog synthesizers that

have Attack-Decay-Sustain-Release envelope genera-

tors (ADSR EGs), you may recognize the line defined

by R1 and L1 as the "attack" portion of the envelope.

There are parallels between a conventional ADSR EGs

and the DX7's EGs. However the DX7 envelopes are

much more flexible than ADSR types because the DX7

offers 8 precisely programmable parameters (R1, L1,

R2,L2. R3,L3, R4, L4) instead of 4 (A-D-S-R). It's not

really important for you to understand ADSR enve-

lopes when you're programming the DX7, but if you

already do and are curious about the comparison, see

the envelope discussion in the Advanced Program-

ming Notes section of this manual.

When the operator reaches LEVEL 1, it doesn't stay

there. Instead it immediately begins moving toward the

next level in the envelope, LEVEL 2, and it moves to

LEVEL 2 at RATE 2 (R2).

The change from LEVEL 1 to LEVEL 2 can be an

increase in level, or a decrease in level, depending on

the values you have chosen for these points in the enve-

lope. If, for example, you set LEVEL 1 at the mid point,

and LEVEL 2 at maximum, when you play a note, the

level of the operator will increase to LEVEL 1 and con-

tinue increasing to LEVEL 2. If RATE 1 and RATE 2 are

similar, you won't hear two distinct envelope segments.

Instead there will be one smoothly increasing sound.

Suppose, however, that RATE 1 and RATE 2 are quite

different — say RATE 1 is slow and RATE 2 is fast. In

that case, you'll hear a distinct "knee" as the sound

slowly reaches LEVEL 1 and then jumps to LEVEL 2 at

the faster rate.

If LEVEL 2 is lower than LEVEL 1, then the sound

will begin decreasing in level as soon as it reaches

LEVEL 1. falling to LEVEL 2 at RATE 2. If LEVEL 1 and

LEVEL 2 are both set to the same level (other than

zero), RATE 2 has no meaning since the sound is

already at LEVEL 2 the instant it reaches LEVEL 1;

therefore set it to 99. In any case, the sound continues

to move on to LEVEL 3.

The sound moves from LEVEL 2 to LEVEL 3 (which

may be higher, lower or the same as LEVEL 2); the

transition occurs at RATE 3. You may see the similarity

between the second and third segments of the DX7

envelope illustrated (LEVEL 1 to LEVEL 2 and LEVEL 2

to LEVEL 3) and the decay portion of a standard ADSR.

If LEVEL 1 is the highest level in the envelope, LEVEL 2

is lower, and LEVEL 3 is still lower, you have a 2-stage

decay to LEVEL 3. If, on the other hand, LEVEL 3 is set

higher than LEVEL 2, then only the LEVEL 1 to LEVEL

2 segment is a decay, and the LEVEL 2 to LEVEL 3

segment becomes a secondary attack (at RATE 3) to the

higher level.

LEVEL 3 is different than the first two because when

it is reached, the sound does not automatically move

toward the next level. Instead, the sound remains at

LEVEL 3 for as long as you hold down the key.. or if a

sustain pedal is used, for as long as you step on the

pedal. LEVEL 3 thus corresponds to the sustain level in

a conventional ADSR envelope.

When you stop pressing on a key (or lift your foot

from the sustain pedal), the sound immediately begins

moving toward LEVEL 4 at RATE 4. It makes no differ-

26